The pervasive sultry sounds and hypnotic syncopations of Latin-America’s artistic heritage have pulsed across the Americas’ diverse soundscapes for decades.

The Sousa Archives’ Gerard Behague and Everett Helm Latin American Sheet Music Collection provides wonderful documentation of these music styles between 1917 and 1969.

The earliest examples of Latin-America’s influence on Western-European art and popular music can be traced to the 1850s with Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s Souvenir de Porto Rico and Marche des gibaros.

By the 1920s, Afro-Cuban habanera rhythms called “Spanish tinge” were influencing New Orleans’ early jazz.

Most notable would be W.C. Handy’s tango section of his St. Louis Blues, composed in 1914.

Between the 1920s and 1940s, Brazilian sambas, such as Boogie Woogie na Favela, Quem te viu!, and Vou deixá o batedô, were performed among Rio de Janeiro’s working-class neighborhoods.

These sambas encompassed several distinct music genres ranging from samba enredo (music for carnival parades) to samba pagode (music celebrating food and dance), samba de roda (traditional Afro-Brazilian music) and samba canção (ballads of love).

With the advent of radio, many of these melodies were broadcast across South America, which disseminated this music to other audiences across the Americas.

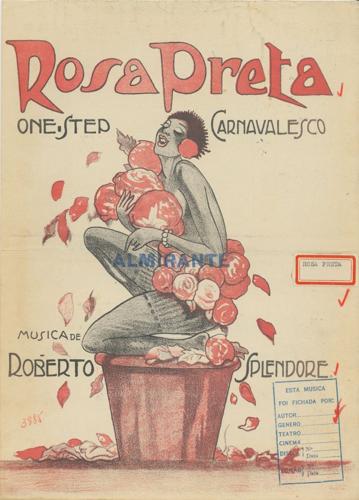

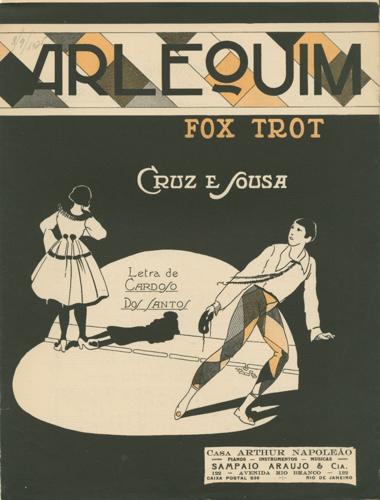

Radio and commercial recordings also carried North American jazz styles to the Caribbean and Central and South America, which enticed Brazilian and Argentine musicians, like swing guitarist Oscar Alemán, to meld these jazz stylings into new tangos and fox-trots like Rosa Preta, Arlequim Fox Trot, and the Ford Que Vôam Tango.

During the 1940s, North America’s swing bands also incorporated Brazilian sambas and Afro-Cuban rumbas and congas into their repertoires.

Stanley Dance wrote in 1950, “Duke Ellington, the supreme jazz colourist (sic), was attracted by it … then Pyramid (1938) on which Duke himself beat a bongo drum, the brilliantly evocative Conga Brava (1940), and the West Indian Dances movement from his Black, Brown, Beige Suite (1943)” drew inspiration from these Latin rhythms.

The fusion of North American jazz and Cuban music by Mario Bauzá and Machito’s Afro-Cuban Orchestra playing Tanga electrified New York’s 1943 music scene with their new Jazz Caliente vibe.

In 1947, Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo combined bebop and Afro-Cuban dance rhythms into their Manteca and introduced American audiences to what became Cubop.

The St. Louis Star and Times wrote on Sept. 2, 1948, that Gillespie’s “Manteca” (RCA Victor) sounds a lot like one of (Stan) Kenton’s Latin American-styled concoctions, full of instrumental pyrotechnics and varied percussion effects.

It gives Gillespie a chance to run through several sparkling solo passages.

By the late 1950s and ’60s, the new bossa music form was crafted from a blending of Brazilian samba and American jazz inflections performed with the guitar.

This new guitar style, born in Rio’s Copacabana in 1956 with Antonio Carlos Jobim and João Gilberto, shifted America’s tastes to softer syncopated guitar and vocal melodies.

The basso nova’s more relaxed samba rhythms and melodies, influenced by Claude Thornhill’s and Miles Davis’ cool jazz of the 1940s and early ’50s, became a musical counterweight to the more percussive Afro-Cuban jazz styles.

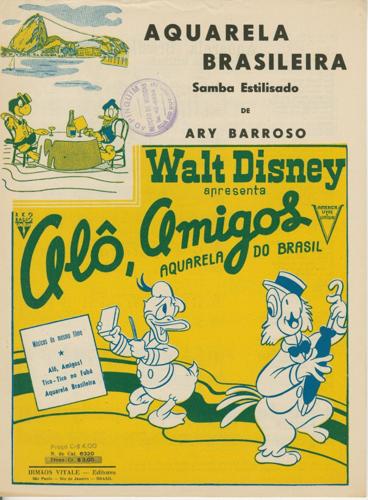

During the 1940s and ’50s, Ary Barroso was considered the most Brazilian of Brazilian composers of his day.

His songs were written and performed by some of Brazil’s greatest samba artists including Carmen Miranda, Silvio Caldas, Elizeth Cardoso, Chico Alves, João Gilberto, Aracy de Almeida and Orlando Silva.

He is credited with creating a new samba genre, samba-exaltação, with his Aquarela do Brasil (Watercolors of Brazil), which was recorded in 1939 and released as a Walt Disney animation in 1942 with Aracy de Almeida as its singer.

His other most recognized samba was Na Baixa do Sapateiro, released in 1938 with singer Carmen Miranda and again in 1939 with Barroso on the piano and Laurindo Almeida and Aníbal Augusto Sardinha, known as Garoto (the Kid), on guitars.

The influence of Brazilian bossa nova on American jazz will be celebrated on April 27th with our “C-U at the Crossroads: International Jazz on Our Doorstep” program which will include a performance conversation at the University of Illinois’ Spurlock Museum (2 to 3:30 p.m.) and a Latin jazz party at Urbana’s Rose Bowl Tavern (4:30 to 6 p.m.). Both programs will feature our community’s accomplished international and local artists José Gobbo and Beto Rodrigues on guitar, Xintian Yu on vocals, Paul Johnston on piano, Max Osawa on drums, and Evani Pluta on bass.

They will be joined by Jason Finkelman and Jenelle Orcherton in casual conversations about their experiences with Latin jazz and bossa nova.

Both programs are free and open to the public.

For those interested in getting a head start on their April jazz exploration, you might also want to catch Darius and Catherine Brubeck’s MillerComm2025 presentation, “Playing the Changes: Jazz and Education in South Africa” on April 23 at 5 p.m. at the Spurlock Museum.

The following afternoon, Darius will be joined by university musicians for a special performance at KCPA’s Krannert Uncorked on Stage 5 at 5 p.m.

For further information about these programs and the center’s Gerard Behague and Everett Helm Latin American Sheet Music Collection, contact Scott Schwartz at 217-333-4577 or schwrtzs@illinois.edu.