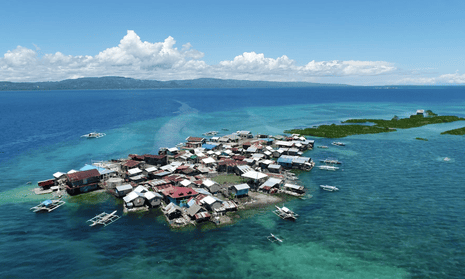

The water laps above her ankles, and flows through her home, sending bottles bobbing gently on the high tide. But Maria Saavedra is unworried, and unmoving.

“I really like it here on the island because it is peaceful,” she says, sitting in the front room of her inundated home on Ubay Island, in the centre of the Philippines archipelago.

The Cebu Strait quietly invades her house on the high tide for nearly four hours a day, more than 130 days a year. But Saavedra doesn’t want to leave the only home she’s known for an uncertain life on a larger island nearby.

“We can eat fresh fish and pick up seashells. We can sell them right away to buy rice … we cook, we eat and then we go to sleep.

“This is where we want to die. We really like this place.”

Chris Chadwick. Hatch

The flooding was sparked by a 7.1 magnitude earthquake in 2013 that caused the land to subside by up to a metre. Now researchers based in Japan, led by Laurice Jamero and Miguel Esteban, are using the islands to examine the environmental, social and economic impacts of extreme sea level rise.

Their research, and the community’s efforts to adapt, are the subject of a documentary Racing the King Tide by Liverpool production house Hatch.

The subsidence has in effect jumped these communities decades forward in time: offering a glimpse of what could happen when sea levels rise to overwhelm low-lying islands.

By 2100, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts global mean sea levels will rise by between 26 and 98cm. The Philippines is a member of the 48-nation Climate Vulnerable Forum, which last month told the UN climate talks last month that islands, communities, even entire nations, faced “extinction” from rising seas.

Adapt and flourish

When the Philippine islands began to regularly and predictably flood on high tides, the Tubigon municipal government launched a relocation program, offering to build permanent houses for the island’s communities on the mainland island of Bohol.

But Ubay islanders are fishers, and their connection to the place they call home is powerful.

The water is central to the islanders’ way of life, and their view of the world. Every 24 June, they celebrate the feast of St John the Baptist – the prophet held to have baptised Jesus in the River Jordan – by taking to the sea.

“We have been celebrating the feast of San Juan like our parents did,” retired fish vendor Servillana Mejares says at her home on Batasan Island. “They told us we should swim in the sea to be healed.

“We don’t stop swimming just because of tidal floods. We are not afraid of box jellyfish. We still celebrate as much as we can. They say the tide will ebb anyway.”

For reasons of economy, social cohesion, and fundamental identity, almost all residents have chosen to stay, for now.

Life goes on: market vendors manage their stalls, domestic animals are moved to bamboo platforms, schoolbags are lifted from classroom floors. In houses that flood, furniture is modified with longer legs, and outdoor cooking fires are raised onto purpose-built scaffolds.

Water – too much and too little – creates manifold problems. The saltwater kills garden vegetable plants, but there’s little that is fresh to drink. The islanders drink purified water and rely on rainwater for their homes, but it regularly runs out and supplies have to be sent from the mainland.

Jamero, lead researcher from the University of Tokyo, said the dominant discussion about sea-level rise focuses on “people fleeing the sinking island, the ‘end-of-the-world’-type narrative”.

“But when I went to these places, it’s completely different. People don’t want to leave their homes, they have found a way to live their lives, to adapt, even to enjoy the floods.”

Jamero said staged relocations – where people move to larger islands for forecast major weather events, such a king tides coinciding with typhoons – was negotiated between the islanders and government officials.

“What really struck me was how the government really listened and actually changed their approach,” Jamero said.

The Tubigon government has focused on education, offering scholarships to high school and college students from the islands, in order to induce relocation more naturally, over two or three generations.

Following the earthquake the government “was really pushing for … the islanders to be relocated to the mainland,” Tubigon municipal administrator Noel Mendana says.

“But islanders think that they cannot survive on the mainland, as their livelihood depends on the sea. So what the government is doing is trying to help them to adapt.”

‘We eat seashells’

Those on the islands have, for the most part, learned to live with the regular inundation, but it does pose significant problems. They understand too, that while they have so far found ways to adapt, their futures, and those of their children, might ultimately lie elsewhere. In the meantime, the islanders make the best of it.

Quick GuideWhat is the Upside?

Show

Ever wondered why you feel so gloomy about the world - even at a time when humanity has never been this healthy and prosperous? Could it be because news is almost always grim, focusing on confrontation, disaster, antagonism and blame?

This series is an antidote, an attempt to show that there is plenty of hope, as our journalists scour the planet looking for pioneers, trailblazers, best practice, unsung heroes, ideas that work, ideas that might and innovations whose time might have come.

Readers can recommend other projects, people and progress that we should report on by contacting us at theupside@theguardian.com

Agnes Bulilan teaches at Bilangbilangan Elementary School, standing barefoot and calf-deep in water, her students perched on stools out of the sea. Classes cannot be cancelled: because the flooding is routine, too many days of school would be missed.

“Whenever we teach and there’s high tide,” Bulilan says, “the attention of the kids is not here anymore, it’s with the sea … they are looking at you, but they are playing with the water with their feet. There is also dirt, it’s fine if it’s just fish that enter the classroom, but… human waste, also enters.”

Chris Chadwick, Hatch

Nutritionist Amelita Sucano on Pangapasan island says regular inundation makes it harder to find fresh fruit and vegetables. Almost all of the communities’ gardens were completely washed away by Typhoon Queenie in 2014.

“Vegetables are rare, we have to get them from the mainland. We usually eat fish and crab, but if there is no fish catch, we eat seashells [molluscs] ... but our biggest problem is tidal flooding, when the plants are splashed by seawater they wilt,” she says.

Shooting on the tiny islands, film-maker Chris Chadwick from Hatch said he was struck by the islanders’ adaption to their new world.

“When you arrive, there’s an initial shock at how drastic the experience is. The home we used as our base was someone’s front room, with all the seats and sideboards propped up. Within two-and-a-half hours the same room was filled with water, and a kid, 18 months or two years old, was swimming in it, with no fear at all, a little water baby.”

Racing the King Tide is a a collaborative research project between Waseda University, The University of Tokyo, Liverpool John Moores University and production company Hatch. It is screening as part of the BFI’s Future Film Festival on the Southbank between February 21 and 24.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion