The WP-3D Orion aims right for the hurricane, its four props spinning against a cloud-darkened sky. It's September 22, and the crew inside is flying toward a monster storm named Maria as it swirls off the Atlantic coast.

They're riding inside a converted submarine hunter nicknamed Kermit the Frog, one of two operated by NOAA (the other is called Miss Piggy.) These planes carry Doppler radar and drop probes to study hurricanes from disturbingly close vantages. But on this flight, they're carrying something new: five-foot-long drones called Coyotes that can be launched from the airplane.

The airplane has a tube that it uses to drop sonar sensors and find subs. The slender unmanned aircraft slides out of this chute. Once free of the six-inch tube, the Coyote's wings unfold and the engine buzzes to life. The drone and airplane head for the storm.

If You Fly It, They Will Come

Joe Cione sits at a console inside the airplane. He's a hurricane researcher at NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. He's also the chief scientist and primary cheerleader of the agency's Coyote research program.

This is the biggest test of the hurricane-hunting drones, and he's got two full days of drops and data analysis ahead, all done at altitude while flying through a hurricane. But this is it. After these 7 drones are launched, the program will be out of hardware and out of funds. Specific Congressional funding dried up years ago, and his program has gotten by since by scraping together money from inside NOAA and from the Navy. This storm is the last chance to prove the drone concept will work. Cione has taken what he calls a Field of Dreams approach to the future. "If you fly it, they will come," he says.

The Coyote dives into the storm's eyewall as the P-3 flies a complementary pattern nearby, circling the eye of the storm. The drone's creator, Raytheon, outfitted it with a data link that allows it to stream sensor data back to the P-3D out to a distance of about 60 nautical miles.

The drone faces intense winds, and flies with the direction of the spinning eyewall. Buffeted by the winds and recovering from occasional, crazed barrel rolls, the drone nevertheless survives to beam data back to the plane. The drone operators slew the craft in S turns, hunting for the maximum wind speed, or Vmax (maximum velocity.) And they find it on that flight—123mph. The wind speed is higher than expected, and within 5 minutes the airplane beams the news to the National Hurricane Center. Forecasters use the updated data, which influences the wind damage estimates, storm surge estimates, and evacuation plans.

The crew flies the drone as low as 300 feet above the water, an area of critical importance for storm formation and a place that usually eludes direct measurement. The Coyote's flight lasts 43 minutes before the brave UAV hits the surface of the Atlantic.

There's no time to mourn or celebrate. There's a storm below, and six more UAVs to launch. Each one is precious to Cione and his team. "I feel this is where hurricane research needs to go," he says. "But we have no resources for more."

Hurricane Hunters

This year's spate of strong Atlantic storms, including Harvey, Maria, and Irma, has once again put hurricane hunters in the spotlight. NOAA has three manned airplanes designated for the purpose: the two P-3s and a Gulfstream nicknamed Gonzo. Gonzo, a mainstay of storm response, has been knocked out of commission three times while responding to hurricane Maria. In one case the seal of a doorway failed, forcing an aborted mission. "There is no backup aircraft to gather this information if and when it experiences technical issues," the Washington Post reports.

It may seem unfair, but Gozo's unreliability does highlight the problem with manned aircraft. They are complicated, since they have to have life support systems and be pressurized. They are limited by pilot endurance. And they are more expensive, making them more rare. Expense usually eats away at redundancy, so when one plane has problems, NOAA suffers.

Meanwhile, a robot airplane seems eager to take over some of the ailing Gulfstream's duties. NASA and NOAA announced a program to use the Global Hawk drones to fly over storms as they develop, studying their intensification for long stretches of time. "With Global Hawk flying at altitudes of 60,000 feet, the team will conduct six 24 hour-long flights, three of which are being supported and funded through a partnership with NOAA's Unmanned Aircraft Systems program,"NASA said in a release.

The Global Hawk is carrying a microwave instrument that takes vertical profiles of temperature and humidity and releases probes that profile temperature, humidity, pressure, wind speed, and direction as they drop. It's also carrying (for the first time in the UAV) an X-band Doppler radar that observes vertical velocity of a storm system.

[youtube ]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXdNB7gUUcE[/youtube]

But while the Global Hawk program is moving forward with NASA partnership, its smaller drone cousins, the Coyotes, face a more uncertain future. Cione says that the program was born from the aftermath of hurricane Sandy, which devastated the U.S. east coast in 2012. His team tested prototypes in 2014 in hurricane Edouard and flew again in hurricane Mathew in 2016. After proving the drones could survive a hurricane, Cione "dug in the seat cushions" for more money. NOAA's department of Ocean Atmospheric Research supplied some support. Less typically, so did the Pentagon.

Luckily for NOAA, the Coyotes have become darlings of the defense world. Raytheon is making steady improvements, including expanding the drone's battery life and brain power. The company flew 30 of them in autonomous formation in 2016, sparking interest from armed services. Special Operations Command uses the disposable, air-launched drone to help gunships find targets through clouds.

"Coyote has become the premiere UAV in the tube launched Small UAS market," says Pete Mangelsdorf, director of Raytheon's Advanced Unmanned Air Systems. "Since the successful demonstration in July 2016, there have been a plethora of different opportunities from all of the key DoD services."

The meteorological heritage of the Coyote drone did not escape the attention of the U.S. Navy. The fleet is very interested in hurricane prediction. And so Cione was able to skim a little money from the Navy to support the effort. This season's flights are the last hurrah, the last chance to prove that the drones can not only fly a storm but beam back useful data.

A Problem Like Maria

Cione flew into hurricane Maria throughout September 22 and 23. The Coyotes always produced data, even though two suffered motor problems. Those problems prompted Cione to cancel the last drop, preserving one of the seven Coyotes. The results from the six drops made over Maria testify to the drones' usefulness, Cione says.

For starters, the drone is a step up from the traditional way NOAA predicts a storm's power. The P-3 carries probes that drop with parachutes to measure the storm's intensity. The drops are made using the best data possible, but the location of the readings are hit or miss. There's no guarantee that the dropsonde (which is what these probes are called) will capture the maximum wind velocity. "The Coyote can make S turns, going with the wind, hunting MaxV," Cione says. "It's an MRI instead of a single point snapshot."

The ability to determine exact wind speeds and more exact dimensions of a storm can be vital to forecasts. The team on board Kermit were delighted to later see their wind speeds appearing in the official forecasts. The maximum wind speed the Coyotes measured was 143 mph, recorded at about 1,000 feet of altitude.

Of course, extra data means extra headaches when it comes to computational demands. Weather data can't spread too far or wide without interpretation, and a data deluge alone won't make things any clearer. Lo and behold, Raytheon not only sells the drones that collect this extra data, but a processing system that the company says is "a forecast toolkit that helps meteorologists make sense of the massive amounts of weather data that modern sensors collect."

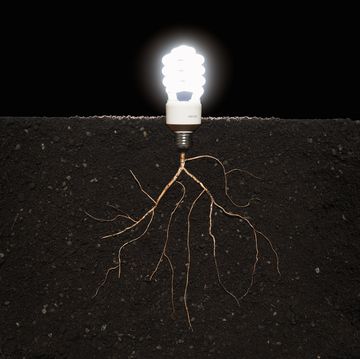

But immediate forecasts are not the only data the drones can collect. The ability to fly low in a hurricane reveals details about the engine of a hurricane: the boundary layer where warm evaporating water energizes the clouds above. Getting a direct measurement so close to the water's surface (and the closer you get, the better the data) is something no sane pilot would want to do. "We've been flying storms for a long time now," Cione says. "But we don't understand the lowest boundary layer."

Computer models used to predict the paths of storms don't take into account conditions at these all important boundary layers. Drones can give scientists the ability to gather data on multiple storms and form a dataset that can create more accurate models.

Lonely Leftover

Every revolution runs on money. Unfortunately, the Coyote program doesn't have any left. "I've got nothing left in the bank," Cione says. "Just one Coyote."

He has a plan for the remaining drone. Using an airplane donated by Raytheon, Cione wants to fly another big hurricane and launch the last Coyote to trace the entire eyewall before darting to the ocean's surface and collect data there. He also wants to use the drone's information to better target the drop of traditional probes into the storm.

After that, he hopes Congress will once again direct funding to the program, finishing what they started after hurricane Sandy struck. He says that attention crests after a storm, making the tests over Maria even more vital. He has seen interest in hurricane research funding ebb as time goes on, until the next storm. "I hate to say that," he says. "But it's true."

For the time being, Cione continues his work as a storm scientist and keeps an eye on the brewing storms to take what he hopes is not the final drone flight into the eyewall. "I feel this is the direction we have to go," he says. "This is a gamechanger."

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.